By Jim Dustin

Copyright DustinBooks LLC, 2014. All rights reserved.

I think at some point the phrase “the lure of the open road” will be relegated to the same niches of American history now reflected in “B” westerns, Civil War romance novels and sitcoms without laugh tracks.

The speed of cars will be strictly governed, breakdowns will be responded to automatically and at fixed fees, GPS systems will guide us unerringly to our destinations, trucks will be incapable of throwing stones or following too closely, and quite possibly, we won’t have to drive at all. We will simply board our “transportation vehicles, or “TVs” and arrive at a pre-determined destination in 6.73462 hours. In fact, Google or someone is “driving” an autonomous car across the nation as I write this – no human driver needed. What fun.

My generation drives. But I expect our grandchildren will say with shock and disbelief, “You didn’t really ever ride in a car going 140 mph, did you?” Many in my generation honestly can say we did. I did in 1968 in a 427, 390-horse powder blue Corvette down Interstate 70 in Missouri. I also drove a Honda 600cc XL motorcycle at over 100 mph on Interstate 270 outside St. Louis.

That wasn’t as fast as the motorcycle would go, but it was as fast as it was going to go with me riding on it. Riding a machine that weighed only 270 pounds at that speed meant that traction was illusory. One sufficiently errant gust of wind, and I would have been down. I was growing up.

But I am still a creature of the road trip generation. When things are getting a little too tense and a little too uncomfortable, you can hop in your car and go somewhere. My first car was a 1964 Chevelle, which was kind of, sort of a muscle car given the right engine and transmission and so on. I never installed speed kits, but it was a three-speed with a standard transmission, and I could spin the tires.

The car was named “Clark,” and it was in no condition to go on road trips. In the future I know is coming, Clark would not be allowed on any road in any civilized nation. But I took Clark on road trips anyway. I was careful to always take the title along in case I had to abandon the car somewhere. I didn’t have enough money for major repairs. I drove it from St. Louis to Charleston, North Carolina – a 1,712-mile round trip – during one blurry summer in the 1970s. At one point, my friends and I were having a contest to see who could leap across the car lengthwise in the fewest steps. That competition left nice dents in the roof and hood but didn’t impair the operability of the car. Insurance didn’t cover the damage because I don’t believe I had insurance back then. I was growing up, but not very quickly.

I still go on road trips. I still go on road trips because I like to travel, but I don’t like to fly. There are too many situations nowadays where one can’t avoid being treated like a head of cattle without voluntarily stepping into such a situation. I learned about road tripping at the feet of legends. These included Al Dedecker, who engineered the 1,000-mile dash from St. Charles, Missouri, to Aspen, Colorado. Or Tom Gee, who went off from Columbia, Missouri, to attend a football game in Boulder, Colorado, yet ended up in Oklahoma. Or John Whitefield, who completed a road trip from Columbia, Missouri, to Lake Havasu, Arizona, by way of Corpus Christi, Texas. He completed the trip, but his car didn’t. Or Jerry Cook, who trusted me and my van to transport his most precious possessions from New Orleans to St. Louis. I thought it would be a good idea to pick up some fresh shrimp at 75 cents a pound and sell it in St. Louis for $1.80 per pound. It would have worked if we hadn’t flipped the van and destroyed the precious possessions and 80 pounds of shrimp, all of which mixed together in a rich, aromatic stew in the back of the van. Or Rich Camp, who managed to fart all the way from Red Lake, Ontario, to St. Charles, Missouri. Ah, the memories.

Not too long ago, I thought my road trip days were over because I was losing my sight. I had just about given up driving at night or even passing anyone due to my deteriorating depth perception. I went on what I thought would be my last trip with two friends – both named Jim – from Walden, Colorado, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana – a 2,714-mile round trip. We drove straight through, there and back. The authorities already are limiting the time a truck driver can spend behind the wheel; in the future I foresee, passenger car drivers will face the same limitations.

Anyway, my sight got fixed through the replacement of old lenses clouded with cataracts with new lenses produced through the ingenuity of the American medical system (pre-Obama). I had a new Honda Pilot that had just proved itself over the 2,714 miles to Baton Rouge and back, I was recently retired, and I had a few extra bucks to blow. The open road beckoned.

Then, as it happened, some friends of mine in St. Charles, Missouri, were drinking perhaps too many beers one night and began planning a road trip from St. Louis to Anchorage, Alaska. Except their road trip would be atop motorcycles. This to me was proof of several, simultaneous midlife crises. These guys were more or less my age, and they were considering a 3,722-mile trip (one way!) across five states and two Canadian provinces through all kinds of weather on motor vehicles that can’t carry a lot of beer. Before I really considered how likely it was that they would actually do this, I said to one of them, “What you really need is a support vehicle.”

Well, several participants became about a half dozen which became a few until finally one disclosed, “That was just the beer talking.” That was in 2013.

The following year rolled around, and I decided that the St. Charles plan looked like a darned interesting trip. The more I looked at it, the more I wanted to go, motorcycle escort or not.

Only one thing deterred me. Me and Hondo the Honda (nearly renamed “The Flycatcher”) were taking a foursome to play golf in Steamboat Springs when the Honda died. Well, it didn’t die, it kind of went into an automotive work slowdown. This happened at a particularly disturbing moment on a two-lane highway when I was in the process of passing a slightly slower vehicle. There was oncoming traffic, so I needed all the speed I could get. What I got was a sudden deceleration and a comment from one of my passengers that “You’d better hurry.”

I had just enough speed remaining to cut in front of the car I was passing and then get off the road. The driver of that car possibly and understandably thought I was an idiot. As it turned out, the problem was a tiny fly – not even a full-size housefly type – had entered an airflow sensor and so confused the CPU that the Pilot could only go five miles an hour … in spurts. It was true, the mechanic told me. A tiny fly had disabled a $30,000 SUV. “And that will be $119 because an outside influence – the fly – disabled the car. Not covered under warranty. The actual part didn’t fail,” said the aforesaid mechanic. It seemed to me that the part had failed in much the same way that an outfielder who had just dropped a fly ball had failed except wasn’t given an error because an outside influence – the ball – caused the glove to fail. But there’s this thing called a “mechanic’s lien,” so I paid up.

This insect threat is a concern when one is planning a 5,000-mile drive through a mosquito-infested part of North America. It is said that the only way to avoid mosquitos in Alaska is to visit in the dead of winter when it is -40º and so there are very few mosquitos.

Going back to my vision of the future, this mechanical aberration wouldn’t be a concern because (a) we most likely won’t even be using internal combustion engines, and (b) roadside assistance would be quickly available after governmental agencies have taken over AAA and other insurance programs. It wouldn’t cost you anything beyond the 76 percent income tax rate that will be common throughout the world.

But we are still in the past as far as that future is concerned, so my concerns remained … for a while. Real road warriors from my generation do not dwell on that which we cannot control. I recall a road trip from St. Louis to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. It was a ski trip, so we were traveling in the deepest part of winter. We were stopped somewhere along the way, and Darryl McGraw asked me, “What are you doing?”

I answered, “I’m checking the weather ahead.”

“Why?” said Darryl. “We’re going to go anyway.”

This is the quintessential road tripper, and his quintessential motto: “We are going to go anyway.” So damn the flies and full speed ahead.

Planning

This view was from my camp on Lake Leberge, Yukon Territory. Canada has scores of similar provincial parks.

The motorcyclists were going to camp along the roadsides on their trip. Say their trip took two weeks. Staying in a motel every night would cost about $1,400 each. Camping costs little or nothing, and it’s not a bad plan for the western United States and Canada. The U.S. has national forests, and Canada has provincial parks. The cost for camping, if there’s anyone actually there to collect the fee, ranges from $10 to $21 per night at any of those public facilities. Or, with the vast amount of public lands in both nations, one could simply pull far off the road and utilize what is called disbursed camping (where legal, of course). I saw a lot of fire rings in some unusual places just off highways. One was on the grounds of a cell tower.

I didn’t want to do the tent thing. Rolling up a tent after a night of rain is just no fun. But the back of a Honda Pilot with one back seat folded down is almost exactly my height. I got one of those roll up mattresses, a couple of pillows and a sleeping bag, and voila, no tent needed. There was even room for my dog’s bed next to my feet (dogs don’t mind smelly feet, especially if those feet belong to its owner. It gives them a feeling of security. My dog frequently sleeps on the floor at home with her head on my underwear).

So that took care of the sleeping arrangements. Then I took seven pairs of socks and underwear. I figured on staying at a motel every sixth day to wash myself and my clothes. I know, you’re doing the math and thinking I only needed six pairs of each, but you have no idea how far apart motels can be in the Canadian bush. Then, two shirts, two pairs of jeans, one hoodie and one anarak. That turned out to be perfect, given the vicissitudes of weather in the northlands. I added a T-shirt, but I figured I’d be buying several as souvenirs along the way. That, and your face kit and whatever medicines you need, like, or are addicted to, and you’re on your way.

Couple things I added at the last minute that proved invaluable. One was mosquito netting. There aren’t really that many mosquitos in August, but there can be in low places. When it’s hot, it’s hard to sleep in a car with all the windows rolled up to keep the critters out. A little mosquito netting and some duct tape (always, always, always, wherever you’re going, whatever you’re doing, take duct tape), and you have a screen door.

Other additions were a gas stove, and an axe. At public campgrounds, you can either buy or get firewood. In the Yukon, firewood is free at provincial campgrounds, but it’s not split. Ergo, an axe (another difficult piece of cargo on a motorcycle, but not in an SUV). And at least once, I had to camp where no outside fires were allowed because of a nearby forest fire. Ergo, a gas stove. Plus, a gas stove is so much more convenient in the morning when one is ready to hit the road and one doesn’t want to mess with even a little cookfire.

Now I have come close to achieving road tripper perfection. Everything fits nicely in the Pilot or on a streamlined cartop carrier. Which means I am not one of those big ass campers, which I like to call “road clogs,” trying to climb a mountain while trailing a long line of cursing, frustrated drivers. And I am not on a motorcycle with no chance of staying dry when it rains.

A regular passenger car doesn’t work. I tried that with Clark the Chevelle. Better to stay in a youth hostel with dozens of possibly disease-carrying strangers than try to sleep in a car. The modern passenger car was designed so no one could sleep in one so that Americans could develop the “motel,” and later invent the station wagon, the minivan, and finally the epitome of road tripping, the large SUV. The all-wheel-drive SUV, I might add. If one happens to be traveling along the Top of the World Highway in the Yukon Territory after a night of rain on a stretch of road where guardrails have not yet been and may never be installed, one appreciates all-wheel drive. And good tires. I spent $846 before I left on good tires, and never had reason to regret one penny of that expenditure.

So I’m ready to go. I was delayed a week because the mayor and good friend Kyle Fliniau asked me to stay and help with some town business, but I finally escaped Walden, Colorado, on August 6, 2014.

Day One

I wasn’t headed for Anchorage. I’ve been to Anchorage and found no reason to return. That might have been due to me being in Anchorage on my honeymoon, which coincided with the first typhoon to ever reach that city in 100 years, two events that were not exactly high points in my life.

I headed for Dawson City. That’s 2,769 road miles, or a 5,538-mile round trip. I would prove to be off by about 1,700 miles, mainly because of the Canadian system of highway signage. More on that later.

This fellow visited my first campsite in northern Wyoming. I thought the visit should reduce my camp fee by one buck.

So Day One takes me north into Wyoming, and I’m not using interstates. Interstates are boring. You can’t see or appreciate much going 75 mph. And I find small towns fascinating. I live in one. I’m a town trustee and an active member of the Lions Club. Driving state highways through small towns might give me some ideas on how my own town might be improved. Or not. See upcoming comments on Hyder, Alaska.

Whenever I start out on a road trip, I do the math. If one is driving from here to there on a schedule, one should figure making 50 mph. It doesn’t matter how fast one drives; it matters how often one stops. If one is traveling with a dog, the number of stops and the duration of the stops vary. No matter how nervous and jumpy the dog is in the car, after you stop, those bowels won’t move until the dog is good and ready. It’s worse with children. I don’t have any children, but I was one once. My dad was a road tripper. I used to be fascinated how he could light a cigarette from a pack of matches using only one hand. It’s a trick I later utilized in college by being able to light a cigarette while standing at the urinal in a bar restroom. One doesn’t impress many ladies in that particular locale, but it’s a neat trick.

My family was driving over one of the most spectacular highways in the U.S. – the Going to the Sun Highway in Glacier National Park – and I was sitting in the back of the car reading a book. My mom yelled at me to put down the book and look at the scenery. I pouted for a while but then got revenge by throwing up down the window well. It’s not all that easy to find a place to pull over while driving the Going to the Sun Highway unless you pull over a 1,000-foot drop. Such tasks as trying to clean puke out of a window well are going to play hell with your travel schedule.

So figure 50 mph, which means it was going to take six days to get to Dawson City if I drove ten hours a day. That’s a lot of driving, but I needed to get over this particular mental hurdle – I wasn’t on a schedule. I didn’t need to drive 70 mph or even 50 mph. I didn’t need to get to Dawson City on Aug. 12, or Aug. 15. I’m retired. My dog’s with me. There’s no need to be in a hurry.

So I meandered up from Rawlins to Riverton, from Riverton to Thermopolis and stopped to see the World’s Largest (allegedly) Mineral Hot Springs. They are pretty big. I didn’t head to Yellowstone because I’d been there several times and I can’t stand getting caught in these wildlife clots. If a larger-than-average house fly lands near a road in Yellowstone, 94,000 cars stop to take a photo of it and show it to their kids. It’s a wonder the larger animals aren’t killed by the sheer volume of Canon fire. The environmentalists complain about the amount of snowmobile traffic in Yellowstone in the winter, and their ceaseless whining resulted in two federal lawsuits and a decision setting the daily number of snowmobiles coming out of West Yellowstone at some odd number like 398. But they never complain about the 20,000 cars, SUVs, RVs, camper trailers, motor homes, pickups with caps, motorcycles and every other kind of vehicle that drives into Yellowstone every day in the summer.

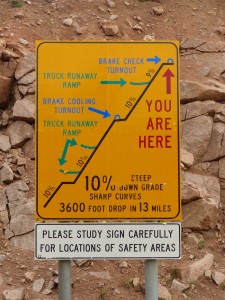

This road coming out of the Big Horn Mountains in northern Wyoming is so steep that the state installed three runaway truck ramps within a seven-mile stretch.

So I headed for the Bighorn Mountains. There’s a loop through the mountains along Highway 14, which I found oddly comforting. A Highway 14 runs through Jackson County where I live. It is also a very scenic route along the Rocky Mountains. I camped in a national park campground where some lady, claiming to represent the U.S. Forest Service, took $10 from me and told me not to let my dog run loose.

“There are moose around here. Your dog will chase one, and the moose will turn around and chase your dog, and you know where your dog will go,” she said.

My dog Abby enjoyed the trip as much as I did, especially when she got to play in a field of wildflowers.

I sometimes get tired of being spoken to as if I were 11 years old and my only defensive weapon is kid puke. My dog Abby has chased many a moose in Jackson County and never once led the moose back to me. But rather than risk a $50 fine, I took Abby about 300 yards east and let her run loose and play in a summer meadow. There are few better mental pictures than that. If you ever lose your dog, dwell on images like that one. Don’t fixate on the death part. I hate dog books that end with the dog dying. So I wrote one where all the dogs come back to life. You can find out how to buy it elsewhere on this here website.

But I digress. I made 398 miles that first day and made my first course correction. A great asset to the road tripper is visitors centers. Most tourist towns have them, and every state has them near the borders with other states. At these places one can get maps, advice on local attractions, and brochures on various Indians and/or trappers and/or explorers and/or soldiers who died horribly in the region. All for free.

I could have, on Day Two, jumped over to Interstate 90 and crossed the border into Montana there. I would surely have found a state visitor’s center where one can also pee, poop, wash up and get weather reports, also for free. I checked with Abby, who had taken to looking out the back window at the scenery as we drove along. Her look said, “More scenery.” So we went back along alternate Highway 14 because it was just so pretty.

Day Two

This is a day of discovery. One discovery is that not all of the western United States is all that interesting. The map of Montana has several state highways labeled as “scenic route,” but unless one is oddly interest in wheat fields the size of Delaware, State Highway 89 is a bust. I kept waiting for the “scenic” along this route, but instead made pretty good time. There was little reason to stop.

There is also a general road rule: you can’t find what you need when you need it. I drove past a thousand campsites during the day, but when night started to fall, I couldn’t find a one. Highway 89 goes through a vast farming region, and I suspected the landowners there wouldn’t take kindly to someone camping in their wheat fields. I had this troubling vision of building a campfire and seeing a floating ember set off a prairie fire in the dry autumn wheat that would make the evening news in several countries. Therefore, it was night when I got to St. Mary, just south of the Canadian border, where I made another discovery: one needs to abandon some equipment along the way. Equipment must earn its passage just like any passenger.

I had a folding chair. It was handy around camp for not only sitting, but also as a step to access the cartop carrier. On Night Two, as I was standing the aforesaid chair, the chair collapsed, nearly ending my trip after one day by throwing me violently to the ground. That chair, I believe, now resides in a St. Mary landfill.

I had also built a little ramp for Abby to use when entering the back of the Honda. I tried to train her to use it at home. She wouldn’t set paw on it. She wouldn’t even walk on it when it sat flat on the ground. What is it with dogs? She would rather jump up on the rear of the Pilot, slightly misjudge, fall on her ass, then try it again rather than walk up a perfectly good ramp that I even equipped with treads. There wasn’t a good place to put the thing in the Pilot while driving, so I finally left it at a campsite in Canada. Either someone found a good use for it, or it became firewood.

At this point I had spent $29 on lodging and $4 on tonight’s dinner. The $4 bought me six ears of fresh corn at an FFA stand along Highway 89. I didn’t need six ears, but some sort of FFA math required that I buy at least six ears. I gave four ears to my neighbors at the campground.

A word about this campground. It was run by two pleasant fellows who apparently had turned their home’s backyard into a campground, one of the benefits of no zoning laws. Access was gained through a gap they had made in their stockade fence – no driveway; one just drove over the lawn. It was organized oddly, but had a grill and a picnic table. Me, my neighbors, and the proprietors all left their trash out at night. Next day, trash all over the neighborhood. I suspect it was a bear, but lesson learned.

Discovery No. 3: if you’re not prepared, prepare to be gouged. Gasoline in Browning, Montana, cost $3.58 a gallon. Gasoline in St. Mary cost $4.09. That, I discovered, was the last gas station before the Canadian border. Had I known the situation, I would have filled up in Browning. But I didn’t.

I’m a capitalist. I admit it. I admire successful people who have earned much money in their lives. But outright, blatant, miserly gouging makes all capitalists look bad and gives fuel to the socialist agenda. See, they’d say, if the government ran that gas station, gas would cost the same everywhere. It would cost much more, but we’d all suffer equally. That’s the essence of socialism – everyone suffers equally. St. Maryans and Browningans would all pay the same price for gas.

I might have agreed with the socialists at that point and flogged myself later for the sin of listening to a spurious argument that has never been proved out in any nation ever, but the gas station proprietor didn’t help. He was the only person manning the cash register, and he was the slowest person at making change I have ever encountered. It required about three minutes per customer. I’m doing the math again. There weren’t that many people in the store, but the line to the cash register was six deep. If you’re sixth in line, that’s 15 minutes to get to the counter.

I just wanted to ask the guy a question, but you didn’t want to do that. If you interrupted his change making, he’d have to start over. Now we’re at five to six minutes per customer, and then this gal at the front of the line says, after her initial transaction was complete, “Oh, and I need a pack of Camels.” I’m thinking, if you’re a smoker, how do you forget that you need a pack of smokes? If the proprietor had had a window well, that would have been the moment to unload that half-digested corn.

Day Three

The Canadian border. I neglected to mention earlier that another piece of equipment I was carrying was a Remington 870 pump shotgun. The Canadian border is a little different than, say, the U.S. southern border in that the Canadians don’t want you to bring guns into their country. The Americans not only don’t mind, they will provide guns to Mexican criminals to bring back into the U.S. as a clever scheme to track down Mexican criminals. Or at least that’s the way “Fast and Furious” was described by Eric Holder’s Justice Department, but I don’t think most Americans quite followed how that was supposed to work. I know I didn’t.

If you google something like “Americans visiting Canada,” you will find a host of things you have to do. You have to have adequate identification. There are certain fruits and vegetables you cannot bring into Canada, nor can you import large amounts of cash. If you’re bringing a dog, the dog has to have papers indicating his rabies shots are current, and even the dog food cannot contain beef byproducts. You can only bring a certain amount of liquor into Canada.

Or, if you don’t want to worry about all that stuff, bring a gun. I really did my homework on this. You cannot bring a pistol into Canada under any circumstances. You can bring a long gun, but the barrel has to be at least 18.5 inches long; it cannot have a foldable stock or a pistol grip; it cannot be fully automatic. You, the gun owner, will be subject to a background check, and you’d better have a good reason for bringing that gun north of the border. You must have prepared paperwork in advance, but the paperwork can’t be signed until you get to the border. And the gun has to have a legible serial number.

My good friend Ben Clayton help me set up the gun after I bought it, and thoughtfully added a shell carrier to the receiver. The shell carrier obscured the serial number. Me and two Royal Canadian Mounted Border Guards spent about 15 minutes trying to figure out how to read that serial number and never could. Fortunately, I’d brought the bill of sale with me, and had a good reason for bringing the gun. “I’m going to be camping out in wilderness areas, and I’m afraid of grizzly bears,” said I.

“So am I,” said the border guard, and he added, “Oh, and that gun has to have a trigger guard. That’s federal law.” That was not mentioned in any of my research. Through sheer good luck, the shotgun came with a trigger guard, which I had with me. Finally, mainly because of my good looks and trustworthy demeanor, they let me through.

Okay, were you following this closely? No questions about the dog or the dog food. No inquiries about booze, or fruits, or vegetables, no questions about how much cash I was carrying, not a word about drugs or prescription medicine. It was just the gun.

Now to cut the RCMP some slack, there were two other fellows from New Zealand being detained at this remote border crossing. After quizzing me about marijuana laws in Colorado, they explained that they were being held up because they were carrying more than $10,000 in cash and the Mounties had detected traces of marijuana and cocaine in their vehicle. Oh.

And I had to fill out a form at the border that included the question, are you male or female. No other choices, not gay, or transgender, or multi-gender, or cross-dresser, or bisexual, or female trapped in a man’s body; just male or female. How odd.

Another thing Canadians do that we don’t do but might have to do is print signs, food labels, trash can operation instructions and other printed communications in English and French. They do this because a bunch of whiny descendents of illiterate trappers in Quebec decided they were being discriminated against because everyone else spoke English. Rather than learn English, they made everyone else at learn French, or at least look at it. This is time-consuming. Reading a highway sign takes twice as long. One has to sometimes back up because he or elle didn’t have time to read the whole sign as he or elle passed only to discover, “Oh, the rest of it is French.” During my entire time in northwesrn Canada, I didn’t run into one person who spoke French or even had a French accent while speaking English.

For those of you who want to U.S. to become bi-lingual, or multi-lingual, this is what you’re going to have to do: change every highway sign in the nation.

There are more and more people in the U.S. who are arguing for a bilingual country, which means we are going to have to reprint everything in English and Spanish at least until the Chinese become a substantial minority here and want the same thing. Except our problem is bigger than Canada’s. For starters, there probably are 1 billion official road signs in the U.S. I’m just guessing; no one knows. If it costs about $100 to change one little sign, which it does, that means the English-speaking taxpayers of the U.S. are going to have to fork over $100 billion to change all the signs. And what if we make a mistake and change them all to English and French? We’d have to spend an additional $100 billion changing them to English and Spanish.

You may have deduced that the highway leading north to Calgary wasn’t all that exciting, except for the canola fields. Most of that part of agricultural Canada looks like agricultural Montana except instead of giant wheat fields the Canadians have giant canola fields, which are bright yellow and much prettier.

Much like the vast wheatfields of Montana, the Province of Alberta has vast fields of canola, which are prettier than wheat.

After getting thoroughly lost in Calgary, I escaped down Highway 1 to Banff, which I didn’t really appreciate because it had begun raining. On vacation, rain doesn’t fall; it sucks. Banff is a beautiful town, but it looked too expensive for me and one mutt. The mutt agreed.

I wanted to travel up Highway 93 through the Banff and Jasper national parks. I thought I’d camp through the night and take my own sweet time driving through these absolutely spectacular mountains. But I missed the turnoff at Lake Louise. If one misses a turnoff in rural Canada, one is not going to realize one’s mistake until the next highway intersection. And the next highway intersection might be 170 miles away. The reason for this is Canadians, possibly for aesthetic reasons or possibly because they have to print all thier signs in two languages, don’t put many highway markers along the highways. Thus, if you are on Highway 1, and you think you’re on Highway 93, you won’t know it until you drive 47 miles in the rain to the city of Golden (Canada, not Colorado) at which point you stop and look at your trip map say to yourself, “There’s not supposed to be a city here.”

So if we go back to that mileage calculation I had made, I just added 94 miles to it driving to Golden and back to Lake Louise, where I eventually found the cleverly disguised “Highway 93” sign, after failing to find it and having to ask directions to it and still ending up driving up someone’s driveway thinking it was Highway 93 and a poorly maintained Highway 93 at that. Honestly, it’s as if the Canadians didn’t want people using that highway.

But this is where I discovered the provincial park campgrounds. These are almost like motels without roofs. They are clean, well maintained and relatively free of bears. A typical campsite will have an iron fire pit, a picnic table and available firewood. Many have tent sites complete with pre-installed ground hooks. Nearby will be vault toilets with oodles of toilet paper (note to campgrounds and sporting venues; don’t use that one-ply, narrow-ass toilet paper because it costs half as much. We’ll just use twice as much). Also nearby will be water, sometimes potable, sometimes not. And the campgrounds are always situated near a lake or a river or some form of natural beauty.

But they are sometimes crowded. Nuff said. Only one time did I have a problem finding a spot. Abby approved of the provincial campgrounds except for the leash laws, which she violated regularly.

I camped next to a group of guys who were partying pretty heavily. Two of them came over and said this was their campsite, but an RV had left the campsite next to their other campsite and they wanted to camp together so they took the RV’s campsite but if the RV came back they would have to take my campsite but it looked like the RV was gone for good. I didn’t follow any of that. I didn’t even know how to register for a campsite, which is kind of cumbersome.

A camper has to find a campsite, then go back to the registration kiosk and fill out a form, put money in the envelope, tear off the tab, deposit the money in an iron receptacle, then return to the campsite and post the tab on a little post. But I thought, what if someone takes my campsite while I’m up here registering? My money would have already been deposited, and if an argument ensues, there’s no one here to arbitrate. I took to leaving my two travel bins at the campsite while I was registering, and that seemed to work.

And the bunch of rowdy guys who were my neighbors turned out to be nice fellows. They were on a “no wives, no kids” outing and whooping it up next to a roaring fire in a soft rain. I asked what their plans were, thinking they off on some ultra-manly excursion.

“We’re taking a bus ride up to the top of a mountain. There’s a meadow up there with flowers that grow and bloom only two weeks out of the year,” they said. Cool.

Day Four

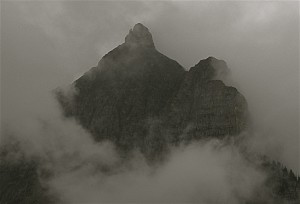

One favorite technique of travel writers is to say that they lack the words to describe what they saw, but then go on to describe what they saw. Using words. One sees phrases like, “Words cannot describe the majesty of these towering mountains, precipitous cliffs, mighty canyons, roaring waterfalls and sparkling rivers that carved stupendous gorges eons ago.” I’ll add another cliché to this lexicon: “cameras cannot truly reflect the majesty of” … and fill in the rest. I’m a professional photographer, but an impatient one. The way to take photographs out here is not to make a quick stop, snap a picture, and move on. One should stay at a site all day or maybe two or three days to wait for the right light. The problem is there are so many places in the West like the Jasper National Park. The Maligne Mountains in The Jasper are a sight any road tripper should aspire to see. It’s as if the mountains in Yosemite National Park and the Grand Teton Mountains got married and had a passel of big kids who all

It’s hard to imagine how much snow is stored on top of this mountain, but I was guessing it 300 feet deep or more.

emigrated to Canada. Sometimes natural beauty is just unrelenting. It got to the point that when I was on the last legs of my trip in northern Idaho, I passed what apparently was a magnificent waterfall on the Kootenai River and decided I’d seen enough waterfalls.

Many moons ago, I had a group of friends in Missouri, and we used to take fishing trips to Canada. I have one of those fish I caught on the wall in my office, a 20-pound lake trout caught near the border of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. The trip cost about $2,500 back then, so my sole souvenir from that trip came in at about $125 per pound. But I didn’t even get to eat it. My trophy is a replica. Lake trout live a long time and mine may still be swimming around up there. I also have tons of photos from those trips, but if one is taking what I call “postcard photos,” they are not much use later in life. I look at those photos of a serene Canadian lake at sunset and have no idea where or when I took that particular photo. I’m already a little hazy on where I took some waterfall photos on my latest trip.

Day Four was also when I began to get a grasp on Canadian math, which is different from FFA math. Canadians use something called a “kilometer” to measure distance. The kilometer was created as a tourism gimmick way back when explorer Alexander Mackenzie wondered if anyone would ever want to live in the northern territories he was exploring. Deducing after one winter that probably no one would want to live there, he figured tourists might work better than settlers to boost the economy.

Thus kilometers and gasoline by the liter, or “litre,” which is pronounced the same, uses the same letters, but “liter” does not look quite as classy as “litre.” If you are a typical American, you look at a sign and see 170, you automatically convert 170 to miles. It’s just habit. But in Canada, the sign that says “Prince George, 170,” means Prince George is 170 kilometers away, which is way shorter than 170 miles. Therefore, you arrive at Prince George way sooner than you thought and exclaim, “Y’know, Canada isn’t that big. We can go further, see more, and spend more money!”

You will also see this wonderful speed limit sign that says 100, and in little, tiny type, “kmh.” You might think that is an enticement to go 100 mph and then get nailed for speeding, but it’s not. I didn’t see a speed trap in the whole of northwestern Canada. I did see some RCMP stations, but I saw exactly two Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers, and they weren’t mounted; they were in a car.

And back to that litre thing. There are 3.7853 litres in an American gallon of gasoline. I generally paid about $1.40 per litre, and that works out to $5.29442 per gallon. So we see why that fellow in St. Mary, Montana, who couldn’t make change at any kind of a normal speed, was actually giving travelers a deal by charging $4.09 a gallon before they went into Canada.

Why this cost differential? Because Canadian governments put a hefty tax on gasoline. On average, about one-third of the total price of gasoline at the pump in Canada is tax. Total minimum taxes vary from 17 cents per litre (64.4 cents per U.S. gallon) in the Yukon to 41.01 cents per litre ($1.552 per U.S. gallon) in Vancouver. Geez, I remember a summer road trip when I was in college that took us from Columbia, Missouri, to Lake Havasu, Arizona. We stopped at Corpus Christi, Texas, to visit a girlfriend. Gas there at that time cost 19.9 cents per gallon. That was 1969. I think the heat in Lake Havasu that summer destroyed some of my brain cells, because I didn’t realize how much gas actually cost in Canada until I got home. However, I am a road tripper. It doesn’t matter what the gas costs; I am going to go anyway.

It could have been worse. There are even more litres in a United Kingdom gallon, but I’m not from the United Kingdom, so I didn’t have to pay that.

And now you know why the Canadians invented the litre. Too many Americans graduating from public school math programs don’t know how to make that conversion, so they don’t know that they’re getting gouged by gas prices in Canada, but that isn’t the worst of it. There is a lodge along Highway 37 in British Columbia called Bell II. I believe Bell I was blown up by irate customers. Highway 37 is the Cassier-Stewart Highway, which is part of the Great Northern Circle Route. That drive should be on the bucket list of every road tripper.

Right at the Bell II Lodge is a highway sign that says something like, “check your gasoline gauge. There are no services for the next 230 kilometers.” It’s a very official-looking sign. So one looks at one’s gas gauge and finds one has 100 miles left, which one doesn’t know how many kilometers that is but it looks bad, so one pulls into the very attractive Bell II lodge for a fill-up and finds the price here is $1.58 a litre, or $5.98 per gallon.

There was a similarly-placed lodge along Highway 93, the Saskatchewan River Lodge, where gas was $1.48 a litre. What this lodge and Bell II lodge have in common is they have no competition within 100 miles of highway, and they have that neat government sign saying “check your gauge.” I don’t know which came first, the signs or the lodges. Gas in all of Canada doesn’t cost that much. They charge $1.11 in Calgary, or $4.20 per gallon U.S.

Here’s a couple of suggestions. To the Canadian provincial governments: allow competition along some of these remote routes. Capitalism does wonders for consumer prices. To the American government: pass a constitutional amendment that says we will not trade with any nation that does not adopt our system of weights and measures.

This is a huge digression from the story of my trip, but honestly, the road from Jasper to Prince George is kind of like over a few rivers and through the woods. I did a lot of thinking about Canadian math along the way and not a lot of sight-seeing.

Day Five

The Great Northern Circle Route begins at Prince George, goes up through Dawson Creek to Watson Lake in the Yukon Territory, drops down to Dease Lake, Meziadin Junction, Hazelton, Smithers, Vanderhoof and back to Prince George. Following this route, the road tripper will travel along all or parts of the Yellowhead Highway, the Cassier-Stewart Highway, the Cariboo Highway and the Alaska Highway, or the Alcan. The road tripper can take side trips off the loop along the Klondike Highway, the Highway at the Top of the World, and spur highways that drop down to Haines, Alaska and the strange town of Hyder, Alaska.

I came down out of the Jasper National Park to pick up Highway 16 – the Yellowhead Highway – to Prince George. I got a sense of what great swathes of British Columbia actually are – uninhabited bush country. The province is like a really, really, really big small town. The area of British Columbia is 364,764 square miles, and the population is 4.6 million. But 2.5 million of those live in Vancouver, and that gives the whole rest of the province a population density of about 12 people per square mile. And most of those live along the paved highways, and the paved highways of any length in northern British Columbia number about six.

Driving from Jasper to Prince George gives one an idea of how vacant most of the area is. I listened to an entire audio book along that stretch of highway and thought about the news of the world that I was getting less and less of at that point. In the age of mass communication, I was becoming increasingly isolated the further north I traveled, and I so wanted to know how many protestors there were on the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, at 11:20 p.m. on Aug. 9 and what they were wearing (if you’re reading this in the year 2021, according to the news media Ferguson was the only thing happening in the whole world at that time).

I lost my cell phone service, I believe, when I entered Canada. Somewhere along the way I attempted to make a phone call, and I got a message display saying “emergency calls only.” Okay, I am something of a Luddite as far as cell phones are concerned, and I don’t have a smart phone, but the phone I had was clearly smarter than me. How, for instance, does the phone know whether a call is an emergency or not? All of British Columbia is not covered by a 911 system. There are signs saying you are leaving a 911 call area. And even more strange, when I crossed the line from Mountain Daylight Savings Time into the Pacific Time Zone, the phone asked me if I wanted to change displayed times to conform to the new time zone. How did the phone know I crossed into a new time zone, could change the time by itself, but refuse to do anything else?

I also began to lose satellite radio as I went further north and west. Satellite radio provides an alternative to regular radio, and regular radio in the northlands is limited pretty much to the Canadian Broadcasting Company. CBC is at times entertaining, and at times not, as was a half hour on how many women were attending an introduction to firefighting school in the Yukon and why. “Well, why?” you ask. Because Yukon women can do anything, one young lady explained. One suspects the reason that Yukon women can do anything is the same as the reason Alaskan women can do anything. The ratio of men to women in Alaska is about 17 to 1, but if you’ve met many of the men in the northern bush country, you would understand why the women say, “The odds are good, but the goods are odd.”

I didn’t mind losing the news so much as I minded losing Major League Baseball. I liked listening to St. Louis Cardinal baseball games while I was making dinner in camp or traveling long stretches of boring highway. But I began losing the signal in direct proportion to how far north I was. I’d just get little bursts of sound, like the excited announcer saying, “Holiday swings and hits …” then silence. I didn’t know if Holliday hit a home run or a long foul ball or the umpire.

It was kind of fun sometimes to fill in the blanks. “President Obama announced today that he …” and I hoped in the silence the sentence concluded, “would resign.” But usually I switched to audio books – I read all or parts of five books while on the trip – or just thinking. A friend of mine, Jay Edwards, got satellite radio because he loves jazz. But he didn’t get it for his car. “When I’m driving, I like to think,” he said. Oh, if only more voters would do that. Imagine a fellow driving to work after reading the morning paper and not listening to Rush Limbaugh (who, by the way, is absent from the airwaves in western Canada) who thinks to himself, “What are the ramifications of what that politician is proposing?” Or in the case of many high school graduates nowadays, “What exactly is a ramification?”

I bypassed Prince George – after getting thoroughly lost in Calgary, I was avoiding big towns – and camped that night on an arm of Williston Lake. I don’t know how many lakes there are in British Columbia; more than ten thousand, I suspect. Many of them are immense. Williston Lake is the seventh largest manmade reservoir in the world. The surface area is 681 square miles. Its dam generates oodles of squeaky-clean energy. It makes one proud to be a human.

Day Six

Not a whole lot to report on Day 6, except that I was looking forward to a motel room. My modus operandi was this; I would stay in a motel room every sixth day, or when it was raining. The third day I got caught camping in the rain because there weren’t any motels along the route that were even reasonably priced.

After five days, one begins to smell, and when one is cooped up in a motor vehicle, there is no place for that smell to go.

In addition to that, I was on this diet I created. I wanted to lose weight on the trip. So my diet was oatmeal in the morning, fruit from markets along the way, and beans and sausage at night. This worked well as a weight loss regimen, but I also became one of the largest methane production facilities in any motor vehicle in North America. I looked in the back of the SUV once and Abby was sleeping on her stomach with her paws over her nose. I was thinking perhaps there might be a way to route this valuable gas from my sphincter to the Honda’s fuel injectors, but I decided it was more advantageous to change my diet.

And one has to be careful driving while farting. Putting this as delicately as possible, one’s fart should consist only of aromatic gases. “Surprise” is defined as a fart with a lump in it. Such surprises can turn an uneventful drive into a halt at a truck stop equipped with showers and possibly laundry facilities. Thus the diet went, so to speak, out the window.

This fellow was carved out of one block of wood and stands on display in Chetwynd, British Columbia, along with other carvings.

My original goal for the day was Watson Lake, but that was far too far for one day’s travel, so my backup goal was Fort Nelson. On the way, I stopped in the town of Chetwynd, the chainsaw carving capital of, as far I’m concerned, the universe. The town’s main drag is lined with the bores of extremely thick trees carved into all sorts of fantastical shapes. The Visitors Center sports about 20 of these wood statues all around it. It’s just astounding artwork.

Then, of course, I had to stop in Dawson Creek. That is the town where the Alaskan Highway starts. The part of this highway that connects Canada with Alaska was built in 1942 by American soldiers to create a surface supply route to Alaska. Despite nearly impossible conditions and total unfamiliarity with the difficulties of building a road in that area of the world, the job was done in nine months. One of the five regiments that did the work was an African-American unit. I don’t need this reminder, I hope, but many Americans do. Blacks in the United States have served this country through generations, thousands of them dying for this country, despite the despicable treatment that was meted out to them in civilian life. Those same blacks that would build a road in terrible climactic conditions to create a supply route to protect Alaska from enemy invasion went home after the war to find – again – that they couldn’t vote, couldn’t go to good schools and couldn’t even drink from the same water fountains as whites. But blacks did and do continue to this day to die alongside whites when the nation needs and asks for their help.

I won’t say a lot about Fort Nelson. The nice gal at the visitor’s center directed me to a motel that was closed for renovation, and the proprietor of that motel directed me to a motel where, among other flaws, the room key didn’t work, but (thank you, says Abby of the sensitive nose), the shower did.

About keys. I worry about keys. Today’s motor vehicles are so sensitive to theft that frequently the vehicle’s owner is the victim of those anti-theft mechanisms. A friend of mine, Brady Carlstrom, owned a Lexus. At a bowling tournament (which was a short but entertaining road trip), a friend of Brady’s – Mike – took a nap (passed out) in Brady’s car, which Brady had locked when he went in to bowl. Mike woke up and couldn’t get out of the car. When he tried to open the door from the inside, everything automatically locked down and the siren went off. Mike had to call Brady on his cell phone to come get him. The language Mike used in the text message was not complimentary to the Lexus image.

An even worse fate was visited upon an angler visiting Lake John, a big fishing lake in Jackson County, Colorado. The man went to the porta-potty, dropped his pants, and also dropped his keys into the stinky sump below. He was four hours from home and only had one set of keys with him. There were few – okay, there were no volunteers who would help him probe the sewage below to find his keys. He eventually called his wife to make the four-hour drive up to Lake John with a spare set of keys.

Me, I know the feeling. When I bought my Honda, I got two sets of keys and ordered three more sets. That’s another thing that separates my generation from current generations. If I wanted extra keys for my 1964 Chevelle, I went to the hardware store and had them made for about a 60 cents each. And if I locked myself out of my car, I and most of my friends could open the door with a coat hanger.

Not now. I told the service guy I wanted three extra sets of keys. He replied that they would be $70 each. Y’see, said he, keys are little computers and they have to be programmed. I said I didn’t care (I did care, but I know my weaknesses), I needed the extra keys. One set would be used every day for the Honda. The master set – the one the dealer needs to make extra keys – would remain in my office. A third set would be in my briefcase, which usually would be in the motel with me in case the regular set accidentally got locked inside the Honda. A fourth key would be secreted somewhere in the framework under the SUV. One can always find a little nook or a cranny where that key can be hidden, and when I lost my driving set of keys on the golf course one day, that hidden key became very important. And there is a final key to replace any of the others I might lose.

So why am I so anal about keys? You have to follow this story closely, because it’s why my golf clubs and a bowling ball got stolen in Grand Junction, Colorado. My previous car was a Dodge pickup with a cap. I was on a road trip to northwestern Wyoming to finish writing a book, and stopped to take a long hike with Abby. I was a couple miles off the highway in the deep forest. I locked up the car. I put the ignition key to the pickup in the bed of the truck, and locked the cap (I didn’t want to drop the pickup keys during the hike; ergo, I left them in the pickup. Some people walk a short distance and hang key in a tree, but what sometimes happens is a group of stupid hikers will come along, find the key, and take it to the nearest town to turn over to the police, which leaves the hikers who hung the key in the tree stranded. Life is sometimes complicated, even for nature lovers yearning for simplicity). I went on my hike. I returned to find I didn’t have the key to the pickup cap. I could see that key sitting on the pickup’s passenger seat. So I didn’t have access to the key I needed to open the cap and get the pickup keys. I had carefully locked away the ignition keys and then punched the automatic lock button to the whole vehicle while the key necessary to get my really necessary key was locked away also. Therefore, I had to break open the cap with a rock shaped like a hammer. I never got the broken lock replaced. When I went on a recreational road trip to Grand Junction, I left my clubs and the bowling ball in the bed of the pickup not even thinking that I couldn’t lock it. Who steals from cars parked in a lighted Comfort Inn parking lot? Well, somebody does.

Now, back to that vault toilet. Given even the remote possibility that something in the pocket of my pants would jump out and land in the sewage below, I remove such items from my pants before I even lift the lid. One day on my trip, it was my wallet. I set my wallet on the toilet paper holder and proceeded with the main purpose of my visit. I walked back 100 yards to camp. Upon arrival, I realized that my wallet was still sitting on the toilet paper roll in a toilet in a campground with 53 camping sites. I am absolutely certain that I set the world record for the 100-yard dash by 66-year-olds as I ran back to that toilet.

The wallet was still there, but I thought, “What if it hadn’t been there?” A good portion of my cash, both credit cards and several other important documents – like my health insurance card – were in that wallet. What if somebody, even an honest somebody, had walked away with it? They would have had no way to find me. People register in these campgrounds by sticking a piece of paper into a metal box. One rarely if ever sees a campground host. And if someone had stolen the contents of the wallet, they would have simply thrown it away. Where would that leave me? I would be like a boxer in the middle of a fight who lost an arm between rounds. One has no conception of how necessary the contents of one’s wallet is until one loses it. At that point, I removed one of the credit cards and hid it in the interior of the Honda. I had plenty of keys to get to it if I needed it.

On the way from Fort Nelson to Watson Lake, I nearly ran into one buffalo, two mountain goats, one bear, one deer and one flagman. The flagman and I had a long chat that started with, “You’ve got good brakes on that car.” I had been gawking at the scenery and nearly ran into the guy. “So where’re you from?” I asked.

“Vancouver,” he answered.

That was about 2,000 miles away from where he was standing on a remote highway, a rather long commute, I thought. “Why,” I asked.

“Job,” he answered. And I pondered, a flagman’s job?

“What does a flagman make up here,” I asked.

“About $800 a week,” he answered. After we got through chatting, I asked if I could leave my resume with him.

I arrived at Watson Lake in the early afternoon. If you don’t know the area, Watson Lake is kind of a crossroads in the north country. Four paved highways come together in the vicinity. I stopped there to load up on freebees at the visitors center, which was run by some of the nicest and most knowledgeable people I’d run into yet.

Watson Lake isn’t a big town, but like several other moderately-sized towns in the Yukon and British Columbia, it had a gimmick. Chetwynd had its chainsaw carvings, Dawson Creek had its Alaska Highway 0 miles marker and living museum, and Watson Lake had its signs

Started by a homesick soldier in 1942, it has become a custom in Watson Lake for visitors to hang a sign from their hometown. There are now 80,000 of them.

In 1942, a soldier working on the Alaska Highway was so homesick, he asked the town fathers if he could put up a sign showing the mileage to his home town in Illinois. Other soldiers started doing the same thing, and after the war and ever since, people have been putting up their hometown signs. At the visitors center, they’ll even give you a kit to make a sign. So now, there are more than 80,000 (not a typo – eighty thousand) signs hanging in the park next to the visitors center. People are just mesmerized by this and spend a bunch of time just wandering among the poles, reading and photographing signs.

I was trying to tell myself not to hurry because chances were I would never be in this part of the world again, and certainly would never be here is such good weather. Since the rain in the Jasper National Park, the weather had been perfect.

So I was going to take the scenic route north of Watson on Highway 4, but the people at the visitors center suggested I not do that. They said the road was pretty rough and not all of it was paved. Hondo the Honda (aka “The Flycatcher”) was wearing a new set of tires, but unpaved roads in northern Canada take their toll. They don’t use limestone for road gravel; they use granite, which is harder, sharper and bigger than the limestone we are used to in the U.S. I don’t know if AAA works in Canada, but I knew my cell phone didn’t work. There’s a point in one’s life where one draws a line between taking chances and taking care. Being stranded on a remote highway in the Canadian bush is not something one enters on the list of “entertaining vacation stops.”

So I took Highway 1 – the Alaska Highway – which starts to bend north toward Dawson City, my goal. That stretch from Watson Lake to Whitehorse is just a wonderful, scenic, fascinating stretch of roadway that I just don’t have the words to describe. Abby doesn’t have the words to describe anything, but she had taken to looking out the back window gazing at the passing parade of verdant vistas and seemed to approve.

This seems like an odd place for a boat. The steamship “Klondike” used to ply the waters of the Yukon River during the gold rush era.

Did I mention every town had its gimmick? As you drive into Whitehorse from the southeast, the first thing you see is a Riverboat from the Gold Rush era. These riverboats used to ply the Yukon River when the Gold Rush was at its height around 1900 and Dawson City was a destination point with a population of 40,000. This particular riverboat is on land at the moment, and one can park one’s car, stroll up to the surprisingly large vessel, and take a tour, all for free. Fun fact: the engines of these riverboats would burn up to one cord of firewood per hour.

Whitehorse, I think, is the largest city in the Yukon Territory, and I actually found a shop with a guy who could sell me a piece of camera equipment that would allow me to transfer photos from my camera (a real camera, not a cell phone camera) to my computer. From there, I could communicate news of my travels to Facebook, and therein lies the reason for this rather lengthy travelogue. I became fleetingly famous on Facebook with some pictures and stories of my trip, so I thought I’d write it all down and post the whole thing on my brand, spanking new website, Dustinbooks.com.

Driving out of Whitehorse, I again took a wrong turn and traveled about 60 miles down the Alaska Highway before I realized my mistake. I had to turn around on Highway 1, then retrace my route back to Whitehorse, then head north on Highway 2. If you’re wondering, all the highways in Yukon Territory run from No. 1 to No. 10. That’s it. Look at the varicose-vein pattern of paved highways in any state in the U.S. – most of which are smaller in territory than the Yukon – and you get an idea how sparsely populated is this grand region of North America.

You also may be wondering why I didn’t invest in a GPS unit before I left on my trip. For starters, I have a flip phone, not a smart phone, and my 2011 Honda Pilot didn’t come with GPS. I bought it “off the rack,” and so couldn’t order amenities. But I wouldn’t have ordered GPS in any case. On that road trip to Baton Rouge, both of the Jims with me on the trip had GPS on their phones. I woke up in the middle of the night, and we were driving down a frontage road about a mile from the interstate. “Why aren’t we driving on the interstate?” I asked. “Go back to sleep,” they both answered at once. It seems the two GPS phones had given conflicting information.

This happened again in Baton Rouge. The Motel 6 where we were staying was located at the west end of a bridge across the Mississippi River. Jim Anderson and I were returning from a golf course on the east side of the river when we got to the bridge. “Turn left,” Jim said. I said, “That can’t be right.” Jim says, “No, left,” and I said, “No, I mean, that can’t be correct,” and he says, “That’s what the phone says,” showing it to me. We’re in traffic, so I had to make a decision, which to me was obvious. We had to go over the bridge. The phone, you see, couldn’t differentiate between one Motel 6 and another, which reveals a deeper problem.

We, as humans, are developing an unhealthy dependence on machines. Having seen Terminator I, II and III, I know where that can lead. It’s not that I don’t trust GPS systems. Heck, I got misled looking for a campground that turned out to be closed. The map I was using misled me (“map,” for you youngsters, is a kind of detailed aerial view of a region printed on paper).

Paddlewheelers plying the Yukon River had to pass this island via the near channel, the wider channel being too shallow. It was a dangerous part of the voyage. I prefer a car.

Maybe if I’d had a GPS system, I wouldn’t have missed the Highway 2 turnoff. Or maybe not. Remember, I have a satellite radio that wasn’t working hardly at all at those latitudes. Maybe that slightly condescending female voice would not have come on and said “recalibrating.” And while we’re on the subject of GPS voices, could we have a little variety? Could we maybe have a fellow with a southern drawl saying, “Ah haite to mention this, but y’all are goin’ to have turn this outfit around and head back thataway.” Or maybe an annoyed black woman saying, “Look fool, this ain’t right! Damn. Turn this thing around, and I mean now. An’ lissen to me next time! Don’t make me recalibrate again or I’ll steer your ass into Lake Michigan!” Or Mae West: “Dahling, if you want to come up to my place, you’re going to have to follow my, um, directions.”

I think I’ll stick to maps and stay away from the other automobile “improvements” that seem to be popping up all over the place. I don’t want a car that allegedly can steer me out of a lane change, or a car that brakes for me, or a car that parallel parks itself. Who do you sue if the car rams into a Lincoln while parking itself? The car? Me? The dumb computer programmer? I’m still irritated about that fly that disabled my $30,000 SUV because its mere presence confused a sensor that reported directly to the car’s CPU without checking with me first. How much control do we want to give up to a … car. Think about this: a massive electromagnetic pulse explosion from a nuclear device, or a solar flare of sufficient magnitude, or even a well-directed pulsar burst from light years away could knock out the planet’s electrical grids at any time, without warning. In the department of climate change, the universe has far more powerful tools than a carbon tax. Could you survive such a celestial event? Wouldn’t you like to have a nice 1964 Chevelle in your garage as backup?

Anyway, I found my way back to Highway 2 (like that was difficult; there are two highways in the area, 1 and 2) and finally found the next campsite. I stayed on Lake Leberge, another one of these Canadian mini seas. Lake Leberge isn’t really a lake, but rather a widening of the Yukon River as it moves north. It was both a highway and a hindrance to the gold seekers headed to the Yukon bonanzas. In the summer, the lake was large enough to be dangerous in stormy weather, and in the winter, ice flows and changing ice conditions also made it dangerous. The lake is mentioned in the works of two giants of Yukon literature, Jack London (“Grit of Women” and “The Call of the Wild”) and Robert W. Service (“The Cremation of Sam McGee”).

As for me, it was the first time I wet a fishing line. I was sitting on a rocky outcrop watching my bobber when a fellow ambled up and said, as all amblers do to all anglers, “Catching anything?”

“No,” said I, “but that’s really not all that important.” And it wasn’t. From that point, I was treated to a wonderful sunset, and the next day, a gorgeous dawn, and I realized I had now endured six entire days without turning on a TV.

Days Seven and Eight

Dawson City. This burg was not very important before the Gold Rush, and isn’t very important now, speaking strictly from the point of view of commerce. As with most settlements, Dawson City owes its geographic origin to the nearby confluence of two great northern rivers – the Klondike and the Yukon.

This looks like an aerial view of Dawson City, but it was taken from a mountainside overlooking the Yukon River.

The Yukon is a curious river. All great rivers head toward the sea. Few don’t make it. There is one in Africa that disappears into the desert sands. But the smart rivers head directly for the sea. The Yukon is the third-longest river in North America, yet it rises about 100 miles from the Bering Sea But it then heads in exactly the wrong direction to get to the sea. It heads east, then north, then northwest, then west, then southwest like a deranged gypsy for 1,980 miles before it finally finds the Bering Sea. “Yukon” is an Eskimo word meaning “not smart river.”

Just the storied names “Yukon” and “Klondike” evoke visions of tough minors, visionary explorers, giant bears, native tribes, intrepid dog teams, fierce winters and discoveries of vast amounts of gold that made some rich but more poor. The chief illustrator of this life at the turn of the 19th Century into the 20th was Jack London, who lived in Dawson City for about a year. The town was the territorial seat of government until the Alaska Highway bypassed it, so the population eventually sank to about 1,600. It has enjoyed something of a resurgence because there is still gold there that, due to recent high prices, can be mined profitably, and tourism. About 60,000 people per year visit the town. In 2014, I was one of them. Incidentally, for you global warming fans, the highest temperature ever recorded there was in 1983, or 23 years before the release of that great work of fiction, “An Inconvenient Truth.”

If you can’t build a bridge across the Yukon River, run a ferry. This one ran 24 hours a day, back and forth, from Dawson City to the other side of the river leading to The Highway at the Top of the World.

I camped in a provincial campground along the Yukon River across from town. There’s no bridge there. A ferry runs 24 hours per day in the summer to take people to and fro. At campgrounds, I take Abby around nearby campsites on a leash. She helps me meet people. I was hoping she’d help me meet as pretty a lady in human terms as Abby is in dogdom. However, she met one of her own. Abby is half boxer, half lab. Her color is black with a white chest and three white paws. Out of a nearby campsite comes a rambunctious brindled dog with a head that looked oddly like Abby’s. I asked its owner what kind of dog it was. “Half boxer, half lab,” he replied. What are the chances of that? I stayed in Dawson City two days, and those two dogs had a lot of fun together. Abby’s getting on in years and can’t hike or play the way she used to, so it was good watching her act like a puppy again.

We’re having a discussion in my hometown about building codes, but our needs clearly aren’t as urgent as those of Dawson City, Yukon Territory, where the only thing holding these two buildings upright is each other.

I was still out of communication with the rest of the world, and I wanted to know what my stocks were doing, so I went to Dawson City looking for wi-fi. Unless you’re a guest, you couldn’t tap any of the motels’ connections, which is an old road trippers trick. Another old road trippers trick is how to get free ice along the highways, but I’m not going to reveal that because I believe it to be illegal. Not that I ever did that.

The public library was closed, so I found a hippie café with wi-fi. Talk about getting sent back in time! I hadn’t seen so many tie-dyed shirts, frizzed hair, sandals, Indian braids, moon teas and smelled the faint, lingering odor of marijuana since my last demonstration in college. Nobody talked to me because I think I looked like a narc. I ordered a concoction from a menu with no prices on it and hooked up to wi-fi. There, I found several messages to call home immediately.

I’m not going to dwell on this portion of my trip too much. The news was one of my best friends – ten years younger than me – had died suddenly and unexpectedly. A couple of days later while driving down a lonely stretch of highway, I got to thinking about good and evil. I believe in God because there is good and evil in the world. God represents to me the forces of good. The major religions teach the difference between good and evil and come down on the side of good. That’s enough for me. Kyle Fliniau was a good man. He wasn’t Jesus Christ, or Ghandi, or Mother Teresa, but he led his life in an exemplary fashion in all ways. He was, to use a cliché, a pillar of the community, and a good friend to many, a generous soul, and hopefully will be remembered with fondness for a long time.

I believe that as long as we remember people, they continue to exist in whatever passes for the next life. Maybe our memories of them are their energy source for a continued existence. I don’t think individuals who have lived pointless, useless, self-indulgent lives on this plane of existence spend a long time on the next one – maybe an hour or two – because they gave no reason for anyone to care about, or remember them following their earthbound years. After death, perhaps their souls are shuffled along to the great galactic recycling bin.

The problem with my belief system is we remember bad people as long as we remember good people and thereby give deceased bad people the energy to continue their existence on the next plane. The ancient Egyptians might have had an inkling about this. If they had a particularly bad actor in their world, they would erase all record of his or her existence. That would have been quite a chore in ancient Egypt where they would have had to erase stones, but they did it. The Romans had the same idea. They tried to eradicate all record of Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known asCaligula, and rightfully so. Obviously, this didn’t always work. Caligula is well remembered and even admired in some circles today. But if this eradication of one’s record of existence on Earth did work in some instances, how would we know? It’s an enigma, kind of like a road hazard of the mind. Thus are the perils of deep thinking while driving at high altitudes after two hours in a hippie café. But I will do my part for Kyle Fliniau by recalling his honorable life until the day I die.

A golf course in Dawson City? Yep. It’s the northernmost golf course in North America with real greens.

I was able to perform one act of remembrance immediately. One of Kyle’s great passions was golf. We used to seek out new and interesting golf courses, and I found one just north of Dawson City. I was headed up to the Top of the World Highway (which is no big deal, by the way, but it is up there) when I saw a sign that said “Golf.” No way, I say. Dawson City’s climate is like my hometown of Walden, Colorado, where we have two seasons: winter and the Fourth of July. But Dawson (as the locals call it) does have a golf course. “It’s the most northern golf course in North America with real greens,” the pro tells me. They let me play before it opened because I whined, “Geez, I drove all the way here from Colorado.” It as fun, and I wished Kyle could have been there. Maybe he was.

Dawson City is about 2,800 miles from Walden, Colorado, by the route I took. Time to turn toward home. I had planned to drive over the Top of the World Highway into Alaska, make a wide circuit through that state, then maybe do some deep sea fishing out of Haines (where I hoped to tour the underwear factory), but Kyle’s death put a time limit on my trip that I hadn’t had before. Kyle was the mayor of Walden; I was the mayor-pro tem. I needed to get back.

Day Nine

I mostly drove today, covering 600 miles from Dawson City to Watson Lake. The days are long this far north, the roads are long, the scenery consistent. Driving along Highway 2 from Dawson to Whitehorse is kind of like a boat ride on a rolling sea.

The land undulates, and the Canadians do their best to keep a road atop those dips and heaves natural to the land. Road construction is the contractor’s perpetual motion machine; the work is never done and it never will be done. Temperatures range from -50º to 90º in one year, and the ground rises and falls, erodes and slides, and water is everywhere, freezing and flowing. It’s a wonder the bulk of the highways aren’t closed during the summer for reconstruction.

Because I have considerable experience driving in frightening winter weather, I can well imagine what winter is like up here. Just the signs tell the tale. There are dozens of “chain up” areas before what one might consider the least of hills. Then there is the “closed to winter travel” which tells one that at certain times of the year, winter wins and man loses.

The only stops I made during Day Nine were to let Abby go out and play. I don’t know that I’d have done much of that when Abby was young because she would take off and run literally over the entire available landscape. I have waited long hours in the Rocky Mountain forests waiting for Abby to return from some ramble, constantly fearful that a mountain lion or a badger might have extinguished that exuberant spirit. Clearly, she always returned or she wouldn’t have been with me on this trip. Now, she can’t do that because she will collapse from a seizure. They call it “exercise induced collapse,” and it can be very severe. On our last backpack, the seizure was so severe, I thought she had died. So no long hikes on this trip.

But short-term romps in the meadows are okay. I thought about not bringing her along, thinking the stress might induce seizures. I have a trusted friend who would have taken care of her. And a dog can be a large inconvenience. Many motels won’t allow them; they have to be locked up on ocean ferries. I didn’t bring golf clubs because I didn’t want to leave her locked in the Honda for hours in the summer. But then again, watching her romp in a field of flowers will brighten anyone’s day. And then again again, when a bear wandered near my camp one afternoon, there was Abby doing her best pit bull imitation, standing stiff legged with hackles up, barking and glaring in the direction of the bear.

And when a drunken Indian at Dease Lake stuck his head in my window and more or less demanded a ride to “the res,” Abby came charging up from the rear of the SUV, and the Indian backed off. That problem got solved fairly quickly. I didn’t know if “the res” was a reservoir or a reservation, but I asked where “the res” was. He pointed. I said, “Darn, I’m going the other direction.” It didn’t matter what direction he pointed, I was going to be going in the other direction.

And Abby’s my dog. Sad moments stick in my mind. Not necessarily tragic moments, or disastrous moments, but sad moments, like seeing your dog trapped behind a fence looking longingly at you as you drive away to go play golf. I would have had that look stuck in my mind for weeks had I left Abby in Walden. And dogs are the best mood control drugs on earth. They look at you when you’re down as if to say, “Why are you sad? I can help. I’m a dog, you know.” A little doggerel for the road:

Where are we going today, Jim,

And what are we going to do?

I don’t care what you say, Jim,

As long as I’m doing it with you!

And, if you leave Abby behind, I can come home and watch her run in circles, wag her stub tail, and look accusingly at me as if to say:

Where did you go and what did you do, and how come I wasn’t there with you?

So on this trip:

Wherever you are, I should be,

Wherever I am, you should be,

That’s why you’re on this trip with me.

I got to what looked like a nice motel outside of Watson Lake where the rooms had everything except a phone and where the rooms cost $159 per night, having just been remodeled and all. The owner was a nice guy, but I said I really needed a phone in a room. I didn’t add, “a cheaper room.” We were sitting in his restaurant with another guy who owned a motel in the town. He had phones in the rooms. And the rooms were cheaper. “This is the friendliest competition I’ve seen in a while,” I commented.

This is where I was introduced to the phone card, because Guy No. 2’s motel was even cheaper if you paid in cash, but then you couldn’t make long-distance calls. Guy No. 1 said just buy a phone card. They’re only $20. So I did. I made several phones calls on the card that night and following nights down the road. When I got back to Walden, I still had 350 minutes available. I may have overpaid for the card.

Day Ten

My original plans called for me to head for Skagway or Haines and do some deep-sea fishing. Because I was on a schedule, that wasn’t going to work. Next trip, I thought. But I did want to fish some of those lakes and maybe have a fresh fish dinner of some sort. So I left the Yukon Territory, where a fishing license was $20, and dropped into British Columbia where a license was $50 for six days, assuming I could find a place to buy one.

The first sign of officialdom on Highway 37 south is Boya Lake, which I imagined was named after some angler hauled in a monster fish and exclaimed, “Boya, boya, boya, whatacatch!”